Retirement is here. It’s all around us. The median age of our clients is almost 70. Stories about clients’ lack of financial literacy and preparedness are everywhere. The top advisors might reply, “My clients are all set.” But what about the other 97% of people not lucky enough or wealthy enough to earn that level of attention from skilled professionals? Most Americans are on their own.

Is it a problem that the financial industry is generally unprepared for the delivery of retirement advice? Or are we content with our “best efforts”? Is it enough to tell people to save more or to tell the adult children of our clients to go pound sand? There are people doing deep thinking about retirement challenges, but most clients will never meet one of those thought leaders and will not qualify for the attention of a great advisor.

No one thinks this retirement planning stuff is easy. In fact, it’s dauntingly complex. There’s an increasing demand for personal service. The numbers of people looking for (and requiring) assistance are rising. Most haven’t prepared for the lifestyle they want and will have to make adjustments in real time.

“Retirement” is more than just a life stage or a financial condition. It’s a complex personal and emotional transition for the retiree that continues until they die. It also requires their family members to get involved in various ways, even though they, too, are new to the experience (and mostly new to the advisor now intimately involved with family matters).

The top advisors will lead the way in this challenge, negotiating the new path forward. They’ll likely be offering not one but a complex array of solutions aimed at moving targets: the client’s needs. The needs of extended family. Truly the work is “craft,” as these top advisors will show us. But craft isn’t something easily scaled to match the greater demand for the advisors that follow.

No matter how mindful a client’s initial retirement plans might be, there will be surprises and failures. The most important questions for planning cannot be answered with certainty. We don’t know exactly when we will die, if we will suffer from dementia or need special care, and we really don’t know what markets will do or where rates will be or what inflation may do to healthcare and living costs. Without solid answers to those questions, we cannot provide comfort to a couple retiring with $500,000 and Social Security. If they have family health and care issues or brilliant longevity, even $1 million might not cut it. And that will be a surprise to most hard working Americans—the vast majority of whom have not saved anything like those sums. And for sure don’t expect any sympathy from government leaders toward someone with half a million in a 401(k), even if that person is still vulnerable.

Given these unanswered questions, it’s likely we’ll need to retool a lot of people’s retirement plans, perhaps many people’s, coming to the inevitable rescue of folks who didn’t get it right the first time or suffered from a healthcare issue or some other financial calamity, anything that might have ruined what were otherwise the best of intentions.

Three Talks

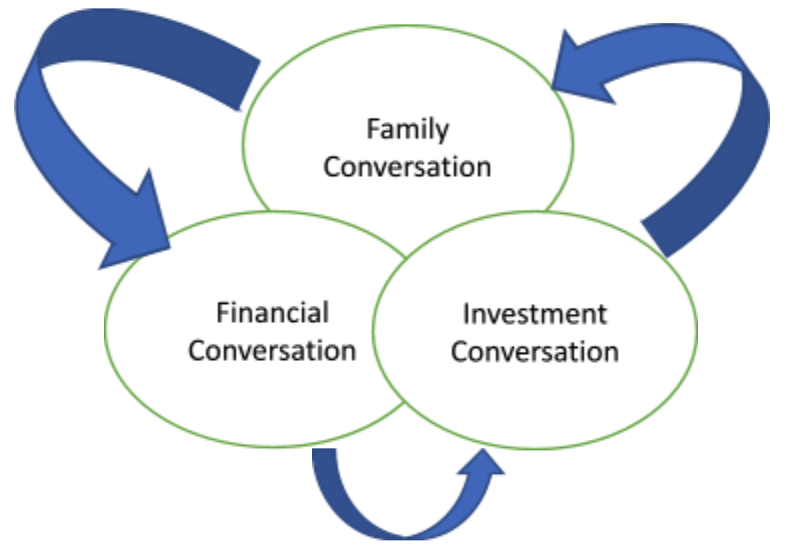

Good planning involves three talks—one about finances, one about investments and one about family. Each of these talks will overlap the others in a Venn diagram, one that’s forged by forces largely outside our control.

The financial conversation. This addresses the nuts and bolts of how much we need and how much we have—the income and expense realities associated with retirement. It will unfortunately involve imperfect projected data inputs flowing from predictions. How much will you spend? How much will you need? Those questions depend largely on when you will die. When is that exactly? Our health is another big wild card.

We seldom calculate with any accuracy how much we have to spend in retirement. We can make hopeful projections about the behavior of capital markets, but do we know what interest rates, inflation or the price of Apple will be in 20 years? What will taxes be? What is the value of Social Security payments over our lifetime? Will cost-of-living adjustments continue? Laurence Kotlikoff, a professor at Boston University and a longtime critic of the retirement planning industry, observes in his excellent new book, Money Magic, the difficulty (futility?) of the financial conversation when retiring baby boomers prefer to keep spending what they want regardless of their available income. Compare corporations, which depend on budgets and then spend accordingly. This simple script flip is a hard calculation and brings many rosy retirement scenarios to a screeching halt.

The financial conversation is the “what” of retirement planning, and it reveals the serious shortfalls in the industry that require attention right now:

- How to manage for the entire family—in a “unified managed household”;

- Tax planning integrated with investments;

- More precise healthcare estimates based on our clients’ actual health;

- Longevity estimates using that personal health data and family history; and

- Liquidity preparedness for big expenses and to minimize disruption.

Perhaps the best overall summary for the plight of today’s retiree is a white paper called “The Peak 65 Generation: Creating a New Retirement Security Framework.” It was written by Jason Fichtner, the head of the Retirement Income Institute at the Alliance for Lifetime Income.

“When people in the Peak 65 generation entered the labor market in 1980,” Fichtner writes, “60% of private sector workers relied on the protected income [from] a pension plan as their only retirement account, as compared to 4% in 2020,” and that “49% of Americans are ‘at risk’ of not having enough to maintain their standard of living in retirement.” And that includes 29% of “high income” households.

The investment conversation. Here the topics represent the planning “how”—how the projected income and expenses will be funded. Like the financial conversation, this one involves considerable forecasting—most notably prognostications about the future performance of markets, interest rates and inflation. Besides investment advisory skill, advisors here can add alpha by talking about the impact of taxes and exchanging assets (for example, selling stocks to fund protected income or selling a home and investing the proceeds) and talk about the sequencing of asset sales (asset location).

We have to talk about taxes, which are for your clients likely the result of investment success. The vexing issue now, for clients and advisors alike, is how to withdraw proceeds from myriad IRAs, rollovers and DC plans. This, after all, is the first native defined contribution generation. How many of them will get that tax help? And from whom? TurboTax?

You’ll need to talk expenses, too. How many clients can outright fund their own healthcare, or long-term care, not to mention a new roof, tuition for a child or grandchild, elder care costs for their aging parents, a wedding? The retirement service industry has come up with liquidity solutions, including generous credit lines against managed portfolios. That access will give some clients peace of mind and feelings of control. But the advisor has to be looking at the total balance sheet. How many do?

There are also benefits such as long-term-care policies tied to life insurance. I have one of those. A trust company CEO told me at lunch recently that his firm encourages local clients to secure a spot in a continuous care retirement facility with assisted living, a nursing pavilion and hospice care. That decision rescued my father when he was told he had pancreatic cancer. Some forms of protected income products leverage client cash better than bonds and add longevity protection. How about the ubiquitous qualified longevity annuity contract with a deferred income annuity (a QLAC with a DIA)? Or how about good old life insurance to leave cash to family members?

What about liberating home equity, one of the biggest assets in the typical household? The largest asset class in the U.S. is residential real estate. That’s about $40 trillion of value waiting to be unlocked, and some of it could make all the difference to one retiree’s balance sheet.

It’s worth asking: How many advisors use these tools and how many clients get the benefits? (It’s also worth mentioning that things like tapping home equity have to be safe, economical and carefully supervised.) If you don’t use all these tools, they’ll likely be used by the 20% of top performing advisors out there (who always inevitably emerge, according to the famous Pareto principle).

The clients themselves may also have opinions about certain strategies and investments, depending on their appetite for risk. But the clients are likely to be both visual and emotional (while their advisors are more likely to be analytical, abstract thinkers). So, for example, when advisors ask clients to “stay the course” during a stock market correction, they’re responding with analytical answers to an emotional reaction (fear). That’s bad bedside manners for the retirement doctor.

The family conversation. If the financial conversation is the “what” of retirement planning and the investment talk is about the “how,” then the family conversation is the “why.” It’s also the “who.”

The retirement journey is really a family affair. The most common retiree family today is a couple with at least one aging parent and adult children and they’re facing demands from both cohorts (a situation that has earned them the name “Sandwich Generation.”)

That means families are affected by the retirement too, and family dynamics become the ultimate wild card. Will aging parents require financial support and time for caregiving? Will an adult child or sibling ask for help? Can retirees handle (or would they say no to) a child’s tuition for a master’s degree, help with a wedding (or a divorce) or a parent’s request for eldercare? Seventy-nine percent of parents are the “bank” for their adult children ages 18 to 34, and the typical support is two times the amount saved annually by those parents for their own retirement.

One trust company CEO I know puts it this way: “It used to be difficult to get our clients to include their adult children in financial discussions, including legacy planning. Covid is clearly one of the influences of change, and now about 60% of our clients are involving those family members.”

There are things we need to do better when it comes to family.

We first need a commitment to effectively engage in the family conversation. Too many spouses are uninvolved in the discussion, too many adult children ignored or not offered a service model more suitable for their digital lives (even though it’s super low maintenance for the advisor).

Yet this is where most advisors bow out. “Human” topics aren’t in their comfort zone. They prefer the mathematics of portfolio analysis. They like the efficiency and simplicity of dealing with the “primary head of household.”

Blow that image out of your mind. Today’s family is three generations—or more—and have a boatload of unresolved dynamics about healthcare and other key life decisions. A couple heading toward retirement is entering new territory for their relationship, and they’ll have to make decisions about their transition—living, healthcare costs, driving and transportation. Who else will help them navigate the changes? Their accountants?

Reality Checks

Ric Edelman says millions of new retirees in pursuit of “quality of life” face serious reality checks ahead. “Whether or not they have an economic need to work, they will have a desire to contribute to American society, keeping busy to remain stimulated, be a member of the community,” he says, as they discover “watching TV and eating bonbons all day is no way to spend the last 40 years of your life.”

The point of all this discussion is not to debate—again—the advantages or flaws of specific elements of retirement planning. Most of the industry enjoys those abstract, analytical jousts. The point—or the question—is to determine our “why.” Are we solving for the needs of our top clients, for our total book of clients? For all the participants of a retirement plan? Do we have a responsibility to improve the results for all consumers? If so, how and when? If not, why not? And—ultimately—if not us, then who?Steve Gresham is CEO and founder of the Execution Project LLC and managing partner of Next Chapter. He was formerly head of the Private Client Group at Fidelity Investments. He also serves as senior educational advisor to the Alliance for Lifetime Income and is the author of The New Advisor for Life.